FORCED LABOUR IN GERMANY

1933 – 1939

During the first years of the Third Reich, German employment offices recruited „non-ethnic“ workers, so-called „civilian“ or „foreign“ workers, in their home countries, mainly in France, the Netherlands, Italy, and Poland. In Germany they were employed in accordance with the valid terms of employment. However, this did not apply to their living conditions because they were housed in barrack camps or kept in separate groups near their place of work. Their supplies of food, provisions, and clothing were also considerably worse than those of the German population.

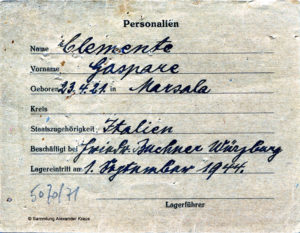

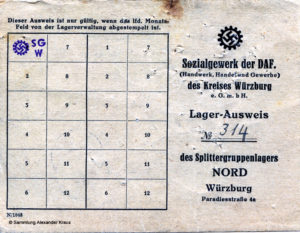

Identity card of an Italian forced labourer who probably came into the German Reich as a prisoner of war.

Beginning of World War II

When these methods of labour recruitment failed to achieve the desired or expected results, and with an increasing demand due to the war, more and more people were deported from their home countries into the German Reich against their will and were conscripted to work. When the war continued, even voluntary workers with an entitlement to holidays were not allowed to leave the German Reich.

From July 1929, prisoners of war were under the protection of the Geneva Convention. It had been agreed that soldiers, with the exemption of officers, could be enlisted to any kind of work apart from jobs in the defence industry. Because Russia had not joined the Geneva Convention, Soviet prisoners of war were usually separated from other POWs and were subjected to more stringent rules.

1939 – 1945

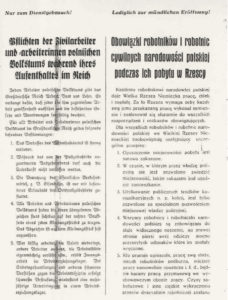

From a legal point of view, foreign workers had no status, they had absolutely no rights, but they were confronted with a catalogue of obligations and prohibitions which they had to fulfill meticulously if they wanted to avoid committing an offence. The Gestapo could have foreign workers sentenced by a court. However, if a drastic sentence seemed likely, the Gestapo often preferred to punish prisoners themselves, for example by imposing a prison sentence or by sending them to a work camp, a penal colony or even a concentration camp.

Forced labourers from Poland, Ukraine and Russia were treated even worse than western prisoners of war and civilian workers because the Nazi racial ideology considered them to be “Slavic subhumans”.

In order to prevent espionage or racial defilement, forced labourers were not allowed to participate in the social life of Germans. They had to keep to themselves all the time.

From 1942, access to air-raid shelters was strictly forbidden to prisoners of war, eastern workers, and people from Poland.

.

Opening of the special Gestapo prison at Friesstrasse on 1 September 1942

Foreign workers and prisoners of war were unscrupulously exploited by most German workplaces and employers. This was often made easy by the workers’ lack of education because many of them could neither read nor write and had difficulties with communicating in the foreign language.

Even smaller businesses had “their” Frenchman or “their” Pole and it was well-known that these people had no rights at all. At the slightest suspicion of an offence they would be treated ruthlessly, arrested, or punished. This can be proved without any doubt by the documents from the special Gestapo prison at Friesstrasse.

Because the Würzburg prison was overcrowded and forced labourers were thought to be too comfortable there, the Gestapo established the special prison at Friesstrasse in September 1942, a barrack camp which complied with the regulations introduced by the Gestapo for concentration camps.

There was a vast scale of offences, e.g. simple theft, assaults against employers, prohibited gambling, forbidden information in letters about events in connection with workplaces, friendly contacts or sexual relationships with German men or women, as well as child abuse. In the case of an assault against an employer, or of sexual relationships or child abuse, labourers were invariably sent to a concentration camp with “special treatment” for most of them, i.e. they were executed on arrival.

During the war about 6,000 to 9,000 men, women, and children were in permanent employment in Würzburg. In most cases they worked in gastronomy, trade and manual jobs, in industry, and in agriculture but some also worked in private households and were exploited there. Many camps and other places for them to stay were established in inns, gymnasiums and barrack camps but some workers also lived in private accommodation at their workplace.

When forced labourers were – rightly or wrongly – charged with offences, we have to take into account that these people permanently lived in exceptional and abnormal circumstances. Often they acted thoughtlessly or out of sheer necessity which can be seen in countless cases.

Certainly not all forced labourers were exploited, humiliated, or maltreated. The Gestapo files only document those cases which resulted in imprisonment for which often simple denunciation was enough. There are many examples that workers were paid well and received help and support. This can also be seen from the fact that, for personal or political reasons, some of them stayed in Germany after the war and established families. Some even protected their former employers against marauding forced labourers and thus saved their lives.

16 March 1945

During the air raid on Würzburg most of the labourers’ camps were destroyed as well as the special Gestapo prison. Many forced labourers lost their lives. It is thought that 120 men and women burnt to death in the prison or were shot dead while trying to escape.

On 21 April 1945, released forced workers from France, Holland, Russia, and Serbia played music and danced on the roof terrace of the student hall in Würzburg which had been the “Goebbels-Haus” of NS students before.

In 2008 the first stumbling stone for a forced labourer was laid in Würzburg. In April 2019 another 21 stones for murdered workers followed at Friesstrasse where the special Gestapo prison had been located.

There is valid information that 317 forced labourers and prisoners of war lost their lives in Würzburg. Some were murdered or died of illness or in air raids. However, in most cases the cause of their death is not known.

There is none or only little biographical information on these victims. Thus no stumbling stones can be placed for them. Therefore any information available is made accessible here.

Author: Alexander Kraus

Translation: Annedore Stassek-Bonnett